Egypt’s Zabaleen & Competing Visions of Privatization

I know even less about this topic than usual but let me say that the evolving story of the Zabaleen is far more inspiring than I understood before our visit, and as good an example I know of how the privatization debate is less over private vs public than the details. It is all about the details.

Many of you know those details better than I. Yet 2 purposes here are to present information in a different way and to provoke comment, especially better informed comment, so:

As mentioned in earlier posts, a graduate planning class is visiting Cairo. At the USAID mission last week, we were told that development workers were surprised to hear that solid waste was a major concern among city residents, even in low income areas. This led to additional funds to support privatization, partly as municipal authorities were doing not a great job and partly because this is often not a municipal responsibility at all. (p.s. USAID aid to Egypt is on the order of $600/million/year.) So there is little concern that privatization — in the form of contracts to mostly foreign trash collection firms — will displace public sector workers, the usual conflict.

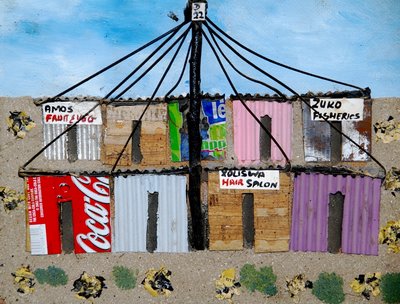

But wait. The 60,000 Zabaleen in Cairo are immigrants, originally from upper Egypt, who for the past 50 years have played a crucial role in the collection of trash, mainly from the higher income parts of the city. For the most part they did this either for free, or by paying for the privilege to intermediaries. Essentially scavengers, driven by abject poverty, they then used the organic refuse to feed pigs, a cash crop.

Their situation has been fairly well advertised in the last decade or so for several reasons: the heartbreak of their precarious, unhealthy plight, their continuing struggles to maintain a hold on their profession in light of the government’s indifference or outright hostility, and the promise of their microenterprise efforts. (They are also used as an environmentally friendly example of sustainable recycling practices.) Examples of the second are decrees to eliminate donkey carts from the city, used to haul trash, or more recent contracts with multinational trash collectors to take over that responsibility in Cairo.

So they have two major problems, among others: The health and sanitation issues associated with living off trash, and the prospect of losing income as the positions of competitors strengthen.

NGOs and international donors have been helpful in both respects, including a couple of particularly generous private donors. Health clinics have been established, as have schools, and the recycling effort has been industrialized to some extent. Much as we did as Vista volunteers in rural Tennessee in the 1970s with local folk arts, assistance has helped brand/promote the products of recycling, such as fabrics (turning rags into quilts, carpets, etc.) and plastics (into raw plastic, toys, etc.), regarding both design and marketing. Math and reading are taught to children by learning to read used shampoo bottles, collection routes, marketing plans, etc., and then by actually participating in these activities. The main effort is focused on education in service of making the profession viable, now in the face of competition from multinational trash companies.

particularly generous private donors. Health clinics have been established, as have schools, and the recycling effort has been industrialized to some extent. Much as we did as Vista volunteers in rural Tennessee in the 1970s with local folk arts, assistance has helped brand/promote the products of recycling, such as fabrics (turning rags into quilts, carpets, etc.) and plastics (into raw plastic, toys, etc.), regarding both design and marketing. Math and reading are taught to children by learning to read used shampoo bottles, collection routes, marketing plans, etc., and then by actually participating in these activities. The main effort is focused on education in service of making the profession viable, now in the face of competition from multinational trash companies.

There are many details I am leaving out. Their religion, a variety of gender-related issues, their land tenure, their local political negotiations, the contracts with shampoo companies to recycle their used plastic containers recovered from the trash in order to limit counterfeit goods that refill those containers, and so on. All these matter greatly but can be discussed better elsewhere. (I will provide sources soon.)

At present, they are principally mobilizing to improve their quality of life and their competitiveness in order to secure a place for their children in the trash collection business. It is not clear how they will fare on either count. However they are, if nothing else, extraordinarily proud and industrious. Making space for this industry in the Cairo political sphere is a genuine challenge, however. As a community of only 60,000 in a city of many millions, they are not a major part of the political calculus, private though they may be.

- Published:

- Monday, April 3rd, 2006

- Author:

- randall Crane

Blogroll

- Becker-Posner blog

- BLDG BLOG

- Burb

- CityStates

- Curbed LA

- Cyburbia

- DemocraticSPACE

- Environmental and Urban Economics

- Freakonomics

- LA Transportation Headlines

- Peter Gordon’s Blog

- Planetizen

- The Center for Land Use Interpretation

- The Transportationist

- the urban commons

- This week’s finds in planning

- Urbanicity

Journals

- Cityscape

- environment and planning a,b,c,d

- Harvard Design Magazine

- Housing Policy Debate

- Housing Studies

- International Development Planning Review

- International Journal of Urban and Regional Research

- International Regional Science Review

- Journal of Architectural and Planning Research

- Journal of Housing Economics

- Journal of Planning Education and Research

- Journal of Planning Literature

- Journal of Regional Science

- Journal of the American Planning Association

- Journal of Urban Affairs

- Journal of Urban Economics

- Planning Theory

- Regional Science & Urban Economics

- Transportation Research Parts A,B,C,D,E,F

- Urban Studies

- World Development

Comments are closed

Comments are currently closed on this entry.