Medieval Inner-City Redevelopment

Field trip to not-sprawl

I am in Cairo with 20 Masters and PhD planning students, toward no real end beyond learning what we can in the time we have about current prospects for the physical city as well as elements of its anti-poverty and pro-environment programs.

As a metropolitan area of 15 million plus, and a history going way back, there is much to know. Still, UCLA PhD student Taha Culhane, who’s lived here several years now, has outdone himself by crafting an extremely full itinerary of places and people.

Development problems

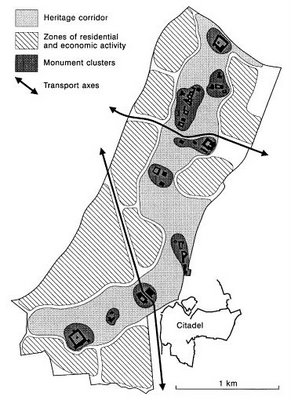

Today we are poking and prodding Islamic Cairo, aka pre-European Cairo. This part of the city mostly dates back to perhaps the 11th to 15th centuries and, in addition to maintaining virtually the same street layout as mapped by Napoleon’s surveyors around 1800, has just over 500 structures remaining of historic “importance.” These include several key mosques, schools, monuments and the like, such as the 12th century Citadel fortress built by Saladin to protect the city during the Crusades.

Such pre-colonial districts are not uncommon in the major cities of the North Africa/Middle East regions, such as the Medina of Tunis, the Casbah of Algiers, and Old Sana’a in Yemen. Their historical (and touristic) value has been well recognized — by some at least — since the early 19th century, with several local and foreign preservation efforts aiming to either restore, renovate, or rehabilitate. Generally, these initiatives cannot said to have been very successful. The primary obstacles are clear: It is enormously expensive, the countries are very poor, there are economic conflicts over the use of the land, they have often been repopulated at higher densities by squatters, and the relative merits of protecting individual structures vs. entire districts continues to be debated. (For example, is it better to restore to original specifications, renovate to modern standards, or rehabilitate to something in between, at the building or block level?) Meanwhile, the structures decline and are demolished.

This part of Cairo has a vibrant economy and several hundred thousand residents, both increasing its value as history and promoting competing uses for its space. (An example of adaptive reuse nearby is the so-called City of the Dead, a pedestrian-friendly cemetery of tombs for the formerly well-to-do, just outside the north wall of Islamic Cairo, now occupied by as many as several million squatters, and growing. It is formerly recognized by the government as a joint burial and residential area.)

No shortage of plans

Sutton and Fahmi (2002) describe several conservation/redevelopment plans, starting with the 1988 Greater Cairo Region Master Plan (which, in planning-speak, referred to this area as “Homogeneous Sector No. 1″). It emphasized “building control regulations,” infrastructure upgrades (a rising water table is a problem for building foundations, requiring drainage improvements), and more open space. In addition, it formally acknowledged the tourism value of the area and sought to relocate wholesale activities elsewhere “whilst keeping retailing and handcraft workshops within the main historical spine.”

The French/Egyptial plans of the late 1980s focused on district-level upgrades, but included several controversial elements for tourism development (e.g., new hotels) and shanty-town relocations that left it a non-starter.

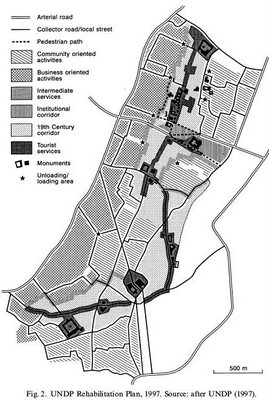

A two-part 1997 UNDP plan also advocated “a tourism-based rehabilitation to restore and reuse monuments,” in a way that would attract private capital. Squatters would be resettled from the restored buildings but to elsewhere in the historic district, rather than the suburbs as in the earlier resettlement plans.

A two-part 1997 UNDP plan also advocated “a tourism-based rehabilitation to restore and reuse monuments,” in a way that would attract private capital. Squatters would be resettled from the restored buildings but to elsewhere in the historic district, rather than the suburbs as in the earlier resettlement plans.

The other major part of the plan was a dramatic departure from the earlier physical plans by focusing on poverty-alleviation.

This rehabilitation exercise would restore and improve local residents’ housing and empower the local community as their education and skills are improved, their built environment is upgraded and as local social services are ameliorated. Monuments would be restored and reused for social services and other community functions. New projects, such as using vacant land to lodge the homeless and squatters, would be labour intensive to provide local jobs. Cost recovery would not be ensured and few profit-generating opportunities would exist for private investors in this approach to rehabilitating the community as well as its built environment. (p. 84)

This included the “pedestrianisation” of the main street and the introduction of more storefront/sidewalk workshops, as well as other public space projects. While focus group interviews with residents raise many concerns about job/market access for relocated industries, and housing security by squatters, all in all the authors like this plan. Yet it too had not been implemented as of 2002.

street and the introduction of more storefront/sidewalk workshops, as well as other public space projects. While focus group interviews with residents raise many concerns about job/market access for relocated industries, and housing security by squatters, all in all the authors like this plan. Yet it too had not been implemented as of 2002.

So Old Cairo now has a promising plan based largely on the principles of rehabilitation rather than just restoration. But action on Old Cairo’s safeguarding remains limited to the piecemeal restoration of a limited number of its monuments and to a few demonstration projects. The ideas are there but the will power, organisation and funding are lacking and more of the historic monuments and the important built environment of this medina area are likely to disappear and crumble. (p. 87)

Perhaps we will be updated later today.

Evening update

One of the benefits of an unexpected rain storm last night was cool weather for antiquities gazing today. In addition to shlepping around the mud of Islamic Cairo, we also benefited from tours and terrific presentations from two leaders in local restoration work: Jaroslaw Dobrowolski, a Polish architect and project technical director for the Antiquities Project of the American Research Center in Egypt, and Seif El Rashidi, an architectural historian with the Aga Khan Foundation. Both organizations are engaged in serious restoration work, though the latter have the larger project by far, as well as a broader scope with jobs and microenterprise banking elements. Nothing at the scale of the 1997 UNDP plan is underway, apparently, though the Aga Khan project in the Dar el Ahmar neighborhood of this part of the city does recognize there are social and economic bases for building abandoment and decay. We were also told that there can be no private sector use of historic buildings, e.g., no coffee shops in restored city gates. Sadly, that would seem to eliminate the profit motive for redevelopment based on such structures.

One of the benefits of an unexpected rain storm last night was cool weather for antiquities gazing today. In addition to shlepping around the mud of Islamic Cairo, we also benefited from tours and terrific presentations from two leaders in local restoration work: Jaroslaw Dobrowolski, a Polish architect and project technical director for the Antiquities Project of the American Research Center in Egypt, and Seif El Rashidi, an architectural historian with the Aga Khan Foundation. Both organizations are engaged in serious restoration work, though the latter have the larger project by far, as well as a broader scope with jobs and microenterprise banking elements. Nothing at the scale of the 1997 UNDP plan is underway, apparently, though the Aga Khan project in the Dar el Ahmar neighborhood of this part of the city does recognize there are social and economic bases for building abandoment and decay. We were also told that there can be no private sector use of historic buildings, e.g., no coffee shops in restored city gates. Sadly, that would seem to eliminate the profit motive for redevelopment based on such structures.

Reference

K. Sutton and W. Fahmi (2002) The rehabilitation of Old Cairo, Habitat International 26, pp. 73-93.

- Published:

- Tuesday, March 28th, 2006

- Author:

- randall Crane

- Topics:

- community development, economic development, Egypt, poverty

Blogroll

- Becker-Posner blog

- BLDG BLOG

- Burb

- CityStates

- Curbed LA

- Cyburbia

- DemocraticSPACE

- Environmental and Urban Economics

- Freakonomics

- LA Transportation Headlines

- Peter Gordon’s Blog

- Planetizen

- The Center for Land Use Interpretation

- The Transportationist

- the urban commons

- This week’s finds in planning

- Urbanicity

Journals

- Cityscape

- environment and planning a,b,c,d

- Harvard Design Magazine

- Housing Policy Debate

- Housing Studies

- International Development Planning Review

- International Journal of Urban and Regional Research

- International Regional Science Review

- Journal of Architectural and Planning Research

- Journal of Housing Economics

- Journal of Planning Education and Research

- Journal of Planning Literature

- Journal of Regional Science

- Journal of the American Planning Association

- Journal of Urban Affairs

- Journal of Urban Economics

- Planning Theory

- Regional Science & Urban Economics

- Transportation Research Parts A,B,C,D,E,F

- Urban Studies

- World Development

No comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss | trackback uri