Dowell Myers on Proposition 13, Demographics and Housing: The New Reality After the Crash

(An essay by USC’s Dowell Myers, summarizing a major report released later today, as noted below.)

Proposition 13 is the infamous tax limitation initiative passed in California in 1978. It launched a nationwide tax revolt (Martin 2008) and also laid the structural basis for Californian’s continuing budget problems. Many have called this the “third rail” of California politics, and belief in Proposition 13 has become a core political value for important segments of the California electorate. What has not been appreciated until the new study being released this week (see Note) is just how much Proposition 13 depends on rising house prices, both for its successful fiscal functioning and also for its voter support.

The Proposition’s origins and cumulative effects over its 30 years are intertwined with California’s soaring house prices. The boom of the late 1970s gave rise to the tax revolt because assessments in those years often rose 60% in a single two-year reassessment. However, the traumatic crash of 2008 calls new attention to our ingrained assumptions about upward price trends. Prop 13, as it is commonly known, was designed for a regime of rising home prices that has now ended. Its two main pillars were a fear of rising prices that drove property taxes to exorbitant levels and the promise that high taxes paid by new buyers would be reduced over time by inflation and made up for by higher taxes paid by other people when they bought at even higher prices in later years. Ever rising prices were the necessary key assumption.

The Proposition has many effects, but the direct impacts on property tax payments were three-fold. First was a rollback of assessed valuations to market values in 1975, a date prior to the major portion of the 1970s boom. After that, second, the annual increase in assessed value would be capped at 2% per year. And finally, third, the Proposition also set a property tax rate of 1% of assessed valuation, which was much lower than currently prevailing in California, 2.6% or 2.7%. The first and second provisions created a generational disparity by benefiting existing home owners at the expense of those yet to come. New buyers in future acquisition years would lock in their assessments subject to the same rules and all would gain increased tax savings to the extent that market values increased faster than 2% per year. But earlier buyers at lower assessments held a lasting advantage for as long as they lived in their homes.

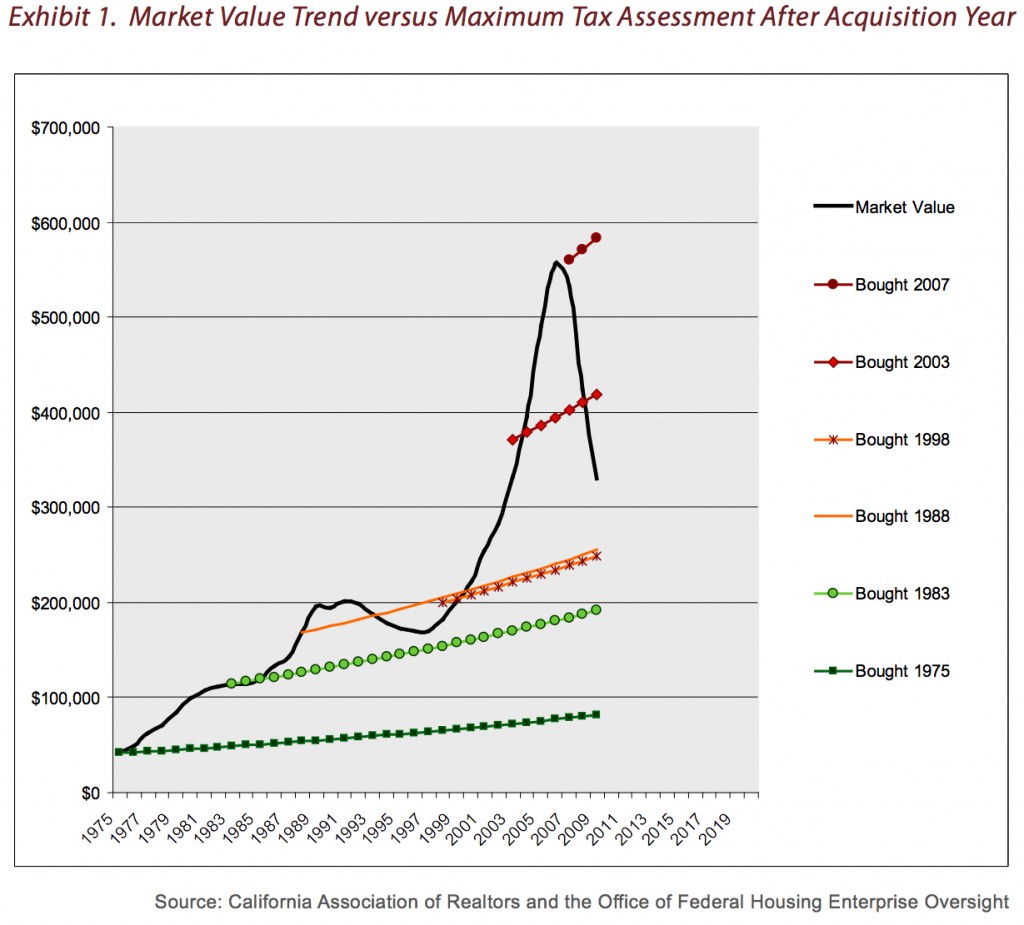

Solutions to the effects of house price volatility were surely needed in California. The extraordinary record of rising prices in California, far in excess of national averages, is portrayed in Exhibit 1. Over the 34-year period portrayed, prices increased more than 10% per year 16 times. Overlaid on the price trend are the trajectories of stabilized assessments enjoyed by buyers in different acquisition years, creeping up at a steady 2% per year. The earlier that a home owner acquired a property, the better the deal under Prop 13. The median sales price in 1975 was $41,600, and in 2009 that property would be assessed at a maximum of only $81,564, if continuously owned. In contrast, the full market value in 2009 is estimated at $329,845, based on the OFHEO constant quality price index series for California. This is a substantial decrease from the peak value of $555,728, in 2006 and from $531,789 in 2007. The 1% property tax on the $81,564 assessment is obviously far lower than taxes paid on the full market value if a new owner were to acquire the same property.

What was long recognized but aggravated today is a severe generational inequity. The older generation now holds a rich advantage, while the younger generation no longer can make up for the seniors’ discounted low payments. The new study being released this week examines the winners and losers by demographic subgroup, focusing on the property taxes and house values of home owners who amount to 74% of California’s voters in 2009.

As long as this system worked as expected, each generation of home owners could benefit, and the rising level of tax payments by new buyers would offset the steep discounts accorded to the earlier buyers. Without the ever-rising levels of tax payments by new buyers, however, the system could not remain solvent. The crash of 2008 has now ended this regime, for the statewide decline in prices by 40% far exceeds that in the only previous downturn in the Prop 13 era (15% in the 1990s). In fairness to property owners whose market values have fallen below assessment, tax assessors are now issuing temporary decline-in-value reassessments — as required by Proposition 8 — that reduce the recent-buyers’ extra high tax contributions. This lost revenue was formerly used to cover the Prop 13 discounts and implicitly subsidize the longtime home owners. Looking forward it seems doubtful that prices and tax assessments will recover to their former level in the next decade or beyond. Until they do, it seems more likely that recent home buyers, state and local governments, and public service users will be left in a depressed state.

Only the longer-time home owners are faring well today. The legacy of Prop 13 is a major generational disparity that has widened over the decades. The generation once thought at risk for eviction from their homes because of high property taxes has now captured a California windfall. Prop 13 may have worked too well: Long time residents now pay lower property taxes than the national average, yet at the same time they have captured much greater wealth from California’s high house values. In a complete reversal of fortune, it is now the young adults who recently bought homes that face risk of eviction.

Some of the key findings from the study are:

Low Taxes but High Values for Long-time Owners

• Comparing California and the US in 2007, home owners who occupied their homes before 1978 paid only $1,571 in property taxes compared to the national average of $1,994. (New Jersey was the highest with $6,155.)

• At the same time, California’s long-time home owners had average home values of $586,409 versus $240,277 in the US, giving them much greater assets.

Young Home Owners are Likely to be Recent Buyers at Risk in the Downturn

• In contrast, home owners who bought their homes between 2003 and 2007 paid $4,787 in property taxes compared to the national average of $2,848. (New Jersey again was the highest with $6,264.)

• House values of California’s recent buyers averaged $564,009 in 2007 versus $289,546 in the US, which presents a high barrier to entry with a new mortgage.

• Of California home owners under age 30, 78.5% bought their homes in 2003-07, as well as 68.5% of those age 30 to 34 and 52.9% of those age 35 to 39. This compares to 19.7% among owners age 55 to 59, for example.

• It is these young recent buyers who are most at risk during the post-2007 housing crash, because they bought at the highest prices and are most likely to have their 2009 house value fall below their tax assessment and even below the principal owed on their mortgages.

Tax Savings from Prop 13 are Very Unequal and Based on Generational Differences

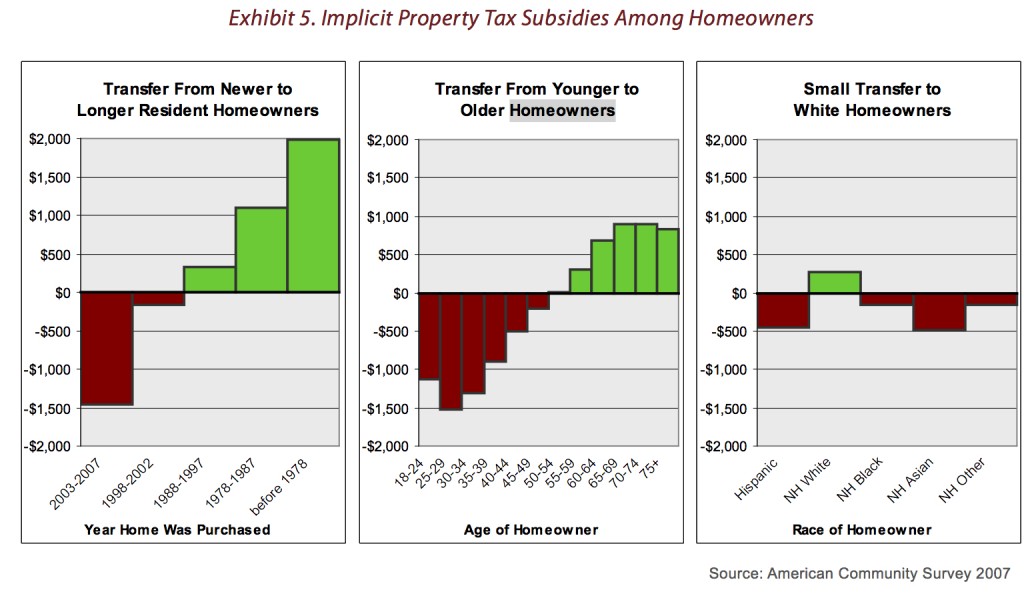

• Tax “savings” defined as the difference between 1% of current value and actual property taxes paid (both as self reported in the American Community Survey) averaged $2317 in 2007.

• The greatest disparities are based on year of purchase, with $4293 savings for occupants since before 1978 and only $853 savings for recent buyers (2003-07), a difference of $3440.

• Other large disparities in savings are found between home owners of different age groups: $3213 for owners ages 70-74 and $796 for owners ages 25-29, a difference of $2417.

• Much smaller disparities are found by race, with only $757 separating the tax savings of the highest and lowest groups. This is because each race contains its own generational differences, which tend to balance out. For example, there is a $2513 difference in tax savings between old and young white home owners.

Recent Buyers and the Young Subsidize the Tax Savings of Others

• Groups with high payments and below average tax savings necessarily subsidize the groups with low payments and above average savings. The subsidies do not come from government but from the contributions of fellow tax payers.

• The largest tax subsidy is provided by recent buyers (2003-07), who contribute $1464 more than average. Longtime home owners paying discounted taxes are the beneficiaries.

• Substantial tax subsidies are also provided by home owners younger than 45 or especially 35, with the beneficiaries being home owners older than 55 or especially 65.

Public Opinion in Support of Prop 13 Depends on House Prices

• Although it is believed that support for Prop 13 is a constant, that may be true only during boom times. Surveys in 1978 and 2008 both registered public opinion after several years of large price increases.

• A 1998 survey by the Public Policy Institute of California tapped public opinion after a period of flat price increases in the 1990s, revealing substantially lower preferences for unequal taxes than was later registered in 2008. Among likely voters, this feature of Prop 13 was favored by 40.1% in 1998 vs. 48.3% in 2008; among renter voters, 25.1% vs. 28.1%; and among home owner voters, 46.3% vs. 56.6%. Increases in support for Prop 13 after the price boom thus were much greater among home owners than renters.

Public Support for Prop 13 is Softer Among the Younger Generation

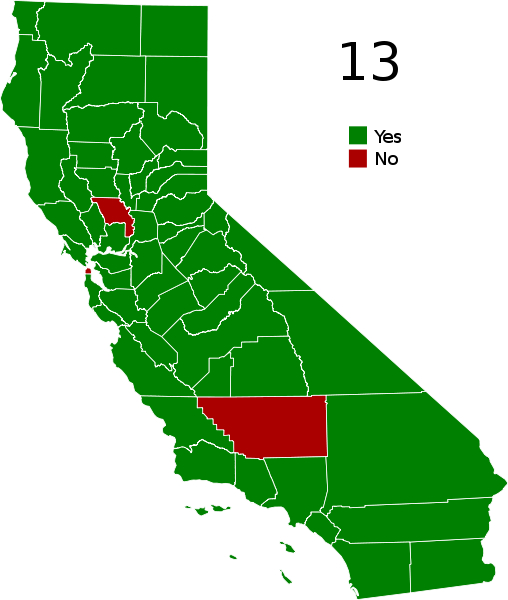

• Asked by the Field Poll if they would vote for Prop 13 if given a chance, fewer of the recent buyers said yes (54%) than buyers who resided in their homes since before 1978 (79%).

• Recent buyers were also much less likely to be very familiar with Prop 13 (29%) than the long-time owners (75%), suggesting they did not yet have a firm position.

• Young voters in fact expressed no opinion on the question much of the time (37% among those under age 40) compared to older voters (less than 10% among those age 60 and over).

Implications for Public Policy

• An education plan is needed to ensure that California citizens understand what is Proposition 13 and the effects of its many provisions.

• Dependency on ever rising house prices is no longer a good basis for fiscal policy. Alternative designs must be explored.

• Continued guarantees against unexpected large spikes in property taxes must be promoted.

• There is an unacceptable discrepancy between longtime owners’ property taxes below the national average and their far higher housing wealth, especially when that discrepancy is supported by extra high taxes imposed on recent buyers who struggle with those high prices.

• Public policy needs to be more future regarding and not simply maximizing benefits for current voters at future expense.

Note The new study, “The Demographics of Proposition 13: Large Disparities Between the Generations and the Unsustainable Effects of House Prices,” is limited only to the question of house values and property tax payments by home owners, who constitute 74% of the voters in 2009. It is not concerned with commercial or rental properties. The study also does not address broader issues of Prop 13, including the effects of tax limitations on service delivery, local control of tax revenues, or the two-thirds voting rule. Preparation of this report was conducted as part of a broader study of California’s changing political demography, with support from the John Randolph and Dora Haynes Foundation. The full report is available here.

REFERENCES

Citrin, Jack and Isaac William Martin, eds. (2009) After the Tax Revolt: California’s Proposition 13 Turns 30. Institute of Governmental Studies and Berkeley Public Policy Press, University of California, Berkeley.

Doerr, David R. (2009) “The Evolution of Proposition 13,” pp. 71-88 in Citrin and Martin.

Martin, Isaac William (2008) The Permanent Tax Revolt: How the Property Tax Transformed American Politics. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Sears, David O. and Jack Citrin (1982) Tax Revolt: Something for Nothing in California. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Published:

- Wednesday, September 9th, 2009

- Author:

- randall Crane

Blogroll

- Becker-Posner blog

- BLDG BLOG

- Burb

- CityStates

- Curbed LA

- Cyburbia

- DemocraticSPACE

- Environmental and Urban Economics

- Freakonomics

- LA Transportation Headlines

- Peter Gordon’s Blog

- Planetizen

- The Center for Land Use Interpretation

- The Transportationist

- the urban commons

- This week’s finds in planning

- Urbanicity

Journals

- Cityscape

- environment and planning a,b,c,d

- Harvard Design Magazine

- Housing Policy Debate

- Housing Studies

- International Development Planning Review

- International Journal of Urban and Regional Research

- International Regional Science Review

- Journal of Architectural and Planning Research

- Journal of Housing Economics

- Journal of Planning Education and Research

- Journal of Planning Literature

- Journal of Regional Science

- Journal of the American Planning Association

- Journal of Urban Affairs

- Journal of Urban Economics

- Planning Theory

- Regional Science & Urban Economics

- Transportation Research Parts A,B,C,D,E,F

- Urban Studies

- World Development

Comments are closed

Comments are currently closed on this entry.