The Meaning and Measure of Sprawl

Planners do not like sprawl one little bit and who can blame them? I once heard urban designer Doug Kelbaugh sneeringly describe sprawl as “a smear on the landscape.” Who likes a smear?

Definitions

Let’s concede that the discussion of what sprawl is and is not covers an awful lot of ground, even if we save space by limiting ourselves to underlying characteristics rather than their consequences. It is not a blog-friendly topic. USA Today says you get close enough just sticking to population density and its rate of change. Smart Growth America (Ewing, Pendall and Chen, 2003) add in land use mixing, highway access and degree of “centeredness.” But if you’ve read Downs’ summaries or Ewing’s 1997 JAPA article, “Is L.A.-style sprawl desirable?” (one of my all-time favorite paper titles because you don’t need to go to the trouble of reading it to guess at the answer) then you already have a start on how the definition can, and should, expand: More detailed density & design elements, the continuity of land development, land use mix, car dependence, circulation patterns, and so on.

This has received terrific attention in textbooks lately, with one or more chapters on definitions in Gillham’s The Limitless City, Bruegmann’s Sprawl: A Compact History, and the explicitly visual (and perhaps visceral) approach in Hayden’s A Field Guide to Sprawl. (Gillham performs the additional service of listing the definitions from a multitude of official constituencies.)

For the sake of argument and economy, one could group these into 3 kinds of smears: Unplanned growth (functional chaos and ugliness), badly planned growth (functional chaos and ugliness), or merely suburban growth in its myriad forms (e.g., low densities, car dependence, enforced homogeneity in form and culture, discontiguous development, esthetic banality,….). Each of these labels has the merit of also suggesting its cause and thus treatment. First, how can we pin it down empirically?

Measures

Planning scholars making signficant advances in the empirical measurement of sprawl lately include Landis, Pendall, and Galster and their colleagues. The real motivation for this post is to also make you aware of a forthcoming 2006 QJE article, “Causes of Sprawl: A Portrait from Space,” by Birchfield, Overman, Puga and Turner. It moves things forward a couple of ways.

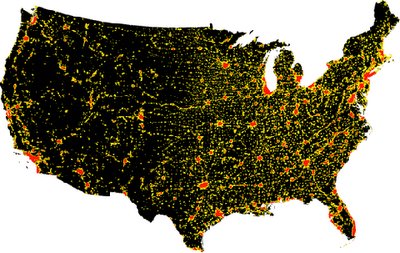

Part 1 is descriptive, with an enormous data processing effort using aerial photos and satellite imagery from two years, 1976 and 1992, for the 8.7 billion 30×30 meter parcels of land of the entire continental U.S. They overlay these two years to measure changes in the amount of developed land, by land use type, resulting in this very cool poster. You can be frightened by the urbanization rate of 2.5% per year over the period (totalling 48% over 16 years) or relieved that by 1992 this still only amounted to 1.9% of the land surface. (That is 2/3rds what Fulton, Pendall, Nguyen and Harrison estimate because, according to Birchfield et al., the more aggregate nature of the Fulton et al. National Resource Inventory data misclassifies large amounts of undeveloped land as developed.)

These averages obscure large differences by place. Coastal areas are more developed, Florida is sprawling faster, and California is sprawling more slowly. Both Atlanta and Miami sprawled quickly but Atlanta mainly via scattered greenfield development at the periphery while Miami sprawled more contiguously or via infill.

Wait, what do they mean by sprawl? Not density. And they aren’t distinguishing between good and bad growth or any design or social capital feature. This is just developed land.

To measure the extent of sprawl … we calculate the percentage of open space in the immediate square kilometer [of each 30m cell]. We then average across all residential development in each metropolitan area to compute … a very intuitive index of sprawl: the percentage of undeveloped land in the square kilometer surrounding an average residential development. (p. 10/11)

Think of each 30m cell as a house. They calculate the % of the square kilometer around that house that is undeveloped, average this over the metropolitan area, and then compare 1976 with 1992. So it is more of a pure land coverage measure than density measure.

The result: In 1976, 42% of the land in the square kilometer surrounding residential develoment was open space. By 1992, this had grown to only 43%. By this measure the country is not tending toward sprawl substantially more than in the past. There is more land covered, to be sure, but much is infill or contiguous. Again, this varies by place.

Part 2 tries to explain these patterns and the rest of the paper is a nice summary of the sprawl hypotheses of modern urban economic theory, physical geography, and political economy; namely, that cities will sprawl more if (p.20):

- they specialize in sectors where employment is not typically located close to the city center,

- they were built around the car rather than around public transport,

- they have experienced slow population growth,

- there is greater uncertainty regarding their future population growth,

- aquifers underlie a greater fraction of their urban fringe,

- they are not surrounded by high mountains,

- terrain in their urban fringe is rugged,

- their climate is temperate,

- they begin with substantial unincorporated areas on the urban fringe,

- local tax payers pay a smaller share of local government expenses.

Most of these are some kind of expectation regarding the relative cost of expanding rather than filling in the urban footprint. Their data seem to support most but not all.??They are particularly surprised by 3 results: The pattern of sprawl is substantially affected by the location of groundwater (future growth tends to stay over the aquifer, as in the past, rather than sprawl) and by the ability to leapfrog out of municipal authority into county authority, while the density of roads does not matter. They have no good explanation for the last result, other than to guess that more road density may stimulate both sprawl and infill, which then wash out in the analysis.??

Right tools for the job?

If you have a nail in your tire, as my wife happens to have today, that means pretty soon you are without a ride. A mechanic could fix it, even a novice.

If you have unplanned growth, that means — unless you are lucky and the natural course of things establishes its own order (as Suburban Nation contends for places like Alexandria, Virginia) — there will be disorder. A planner should be able to fix that too, even an uncreative or uncritical one.

Badly planned growth is accidental disorder. Suburban Nation suggests that an enlightened urban designer (or maybe planners trained by one) is your best bet to fix that.??

Simple suburban growth — such as measured by Birchfield, et al. — reflects, among other things, the pressures of rising incomes and falling transportation costs, terrain/geography, plus governance issues associated with exclusionary zoning (e.g., Zoned Out) and jurisdictional competition/fragmentation. For their part, Birchfield, et al. only suggest the possible value of groundwater regulation and municipal-county land use harmonization as policy initiatives.??

The theoretical appeal of direct controls, such as urban growth boundaries is that they literally draw a line on the map to cage in growth. In practice, however, they may be neither binding (as with the rolling boundary in Portland) nor particularly responsive to the underlying problem — whether that be good vs bad planning, or more fundamental determinants of urban growth.??

Another approach would be to address associated externalities, such as traffic congestion/pollution and the undervaluation of open space. This is always a good idea but is unlikely to be satisfactory to those hoping to make a substantial dent in sprawl. Again, that tack mainly deals with consequences, not causes. It wouldn’t eliminate sprawl, for example, only its excesses.??

Perhaps I need to think about this more.

- Published:

- Monday, February 27th, 2006

- Author:

- randall Crane

- Topics:

- environment, metrics, sprawl, suburbs

Blogroll

- Becker-Posner blog

- BLDG BLOG

- Burb

- CityStates

- Curbed LA

- Cyburbia

- DemocraticSPACE

- Environmental and Urban Economics

- Freakonomics

- LA Transportation Headlines

- Peter Gordon’s Blog

- Planetizen

- The Center for Land Use Interpretation

- The Transportationist

- the urban commons

- This week’s finds in planning

- Urbanicity

Journals

- Cityscape

- environment and planning a,b,c,d

- Harvard Design Magazine

- Housing Policy Debate

- Housing Studies

- International Development Planning Review

- International Journal of Urban and Regional Research

- International Regional Science Review

- Journal of Architectural and Planning Research

- Journal of Housing Economics

- Journal of Planning Education and Research

- Journal of Planning Literature

- Journal of Regional Science

- Journal of the American Planning Association

- Journal of Urban Affairs

- Journal of Urban Economics

- Planning Theory

- Regional Science & Urban Economics

- Transportation Research Parts A,B,C,D,E,F

- Urban Studies

- World Development

4 Comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss | trackback uri