Planning for Global Warming: In the News

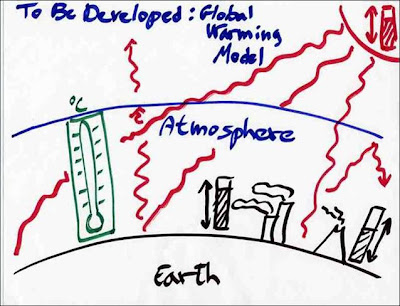

The best illustrated planning research blog on the internets appears to be on summer hiatus but I saw a couple of things this week that, against my better judgment and unforgiving schedule, got me thinking a bit more vis-à-vis Global Climate Change. And What Planners Can Do About It. And What Planning Researchers Advise Planners To Do About It.

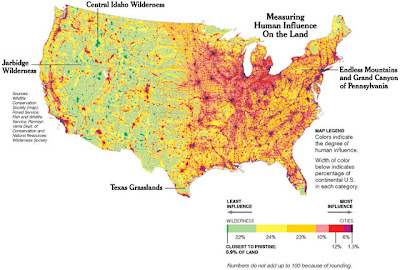

Outline: (A) Jerry Brown sues San Bernardino to plan better for a cooler tomorrow, (B) key details of last week’s negotiated settlement, (C) this month’s Planning magazine on what to do about The Urban Form and Climate Change Gamble, and (D) whatnot. Plus pictures of coolish alternative fuel cars.

(A) Planetizen posted a news brief on a USA Today story in June, titled California Sues Municipalities for Bad Urban Planning:

California is pioneering what could be the next battleground against global warming: filing suit to hold cities and counties accountable for greenhouse gas emissions caused by poorly planned suburban sprawl.

The unprecedented action is being closely watched by states that have taken aggressive steps to combat climate change — including New York, Massachusetts and Washington.

California Attorney General Jerry Brown has sued San Bernardino County, the USA’s largest in land area and one of the fastest growing, for failing to account for greenhouse gases when updating its 25-year blueprint for growth.

If the suit is successful, California cities and counties could be forced to take steps to limit sprawl, promote compact development, require builders to design energy-efficient houses that offer solar power, and encourage less driving, more mass transit and use of alternative fuels.

Commentors were supportive of this action. What’s not to like about saving the planet through sensible urban planning?

Wait, I thought of a couple of things, and said so:

Like everyone, I agree local governments should produce plans consistent with environmental laws. Early coverage of this suit contrasted the efforts of proactive Marin County with those of head-in-the-sand San Bernardino County. But Marin’s plans mainly reflect adaptations to the threat of climate change, by addressing the risk of worsening storm patterns for coastal development in a county surrounded by water on 3 sides.

Landlocked San Bernardino is mainly being blamed for not doing enough to prevent climate change. Fair enough, and pointing out that cars play a big role is fine. How to do this is much less clear. Like it or not, crude efforts to “limit sprawl, promote compact development, and [build] more mass transit” might well produce more rather than fewer greenhouse gases. The academic research and popular press on these issues remain unreliable guides, wishful thinking aside, whenever they suggest the right path is simple or straightforward. I hope the litigation will highlight the need to think hard and well about what will work, not just what people hope will work.

and, in response to another commenter who countered that, “It is well established that people who live in denser cities drive less and (of course) that mass transit emits less CO2 that automobiles per passenger mile,” I recountered with,

… the hows and whys of sprawl and travel are not well established at all, a situation made all the more worrisome when both smart planners and even smarter attorney generals passionately believe otherwise….

Many writers do argue that the sprawl/travel connection is fixed and known. [But] until recently, these studies often have fundamental, undeniable credibility “issues,” especially when generalized to anywhere, any time.

These behaviors and their impacts are proving to be more complicated than we’d prefer. I’m certainly not saying we shouldn’t use planning to address climate change, only that to avoid making things worse we should do it with our eyes as wide open as our hearts.

In defense of my mawkish, unmanly language at the end there, I was under medication at the time, keenly aware of my own mortality, and listening to my grandmother’s collection of sappy country music 45s. (“From now on, all of my friends are gonna be stra-a-a-ng-g-er-r-rs.”) Plus, this is an emotional issue. Suffice it to say that I refrain from such talk in the classroom.

(B) NEWS FLASH: Planetizen summarized a San Bernardino Sun report of a negotiated settlement last week:

A widely watched lawsuit by California’s attorney general against the state’s fastest growing county over the issue of inventorying and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the update of a county general plan has been settled.

“Members of the (San Bernardino) county Board of Supervisors announced on Tuesday (August 21) the end of litigation by Attorney General Edmund “Jerry” Brown, who filed suit against the county in April, alleging that its general plan didn’t include direction on how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The county will work with the state in decreasing emissions through conforming county land-use decisions and operational policies to a reduction target goal – all at an estimated price tag of $500,000.”

“This is a landmark agreement,” Brown said. “This (emissions) problem is so large that no one county can solve it by itself. This plan is extremely innovative.”

“That agreement gives the county 30 months to add a policy to its general plan for reducing greenhouse emissions.

It also gives the same amount of time for adopting an inventory plan for compiling emissions data from 1990, current emissions data, sources of current emissions, projected emissions through 2020, a reduction goal and mitigation measures to meet that goal.

There are no official state guidelines on how counties should approach the issue of global warming, but the agreement helps chart a new path within the issue, said David Wert, county spokesman.”

“It sounds like (the attorney general) sued San Bernardino County to put all of the other counties and cities on notice that local governments should address global warming,” Wert said.

As far as the attorney general’s duties, that office will be responsible for assisting the county in recouping the estimated costs of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the agreement states. It will give advice on projects and assist the county with any legal challenges to its effort.”

Here is a pdf of the (confidential?) agreement where, I gather, the County of SB has agreed to expand their EIR review to include climate change questions, and then to act on them in the form of a “Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Plan,” consisting of:

- An inventory of all known, or reasonably discoverable, sources of Greenhouse Gases that currently exist in the County….

- A baseline inventory of the Greenhouse Gases currently being emitted in the County from all source categories in the inventory….

- An inventory of the Greenhouse Gases emitted in the County in 1990 from all source categories in the inventory….

- A projected inventory of the new Greenhouse Gases that can reasonably be expected to be emitted in the year 2020 due to the County’s discretionary land use decisions pursuant to the General Plan Update…. The Parties recognize and agree that definitive sources do not exist for creating this inventory. Further, the Parties recognize that the projected inventories will include estimates, but agree that the estimates shall be supported by substantial evidence and will represent County’s best efforts. In the interest of conserving public funds, the County will look first to state and regional air quality boards and agencies for the data on which the inventory is to be based.

- A target for the reduction of those sources of emissions reasonably attributable to the County’s discretionary land use decisions…. (p. 2-3, emphasis added)

(C) The August/September 2007 Planning magazine is focused on planning issues in climate change, and is captioned, “Global warming: What you can do about it.” It is all useful reading but the article that first caught my eye was Frank, Kavage, and Appleyards’, “The Urban Form and Climate Change Gamble.” Feeling lucky today?

The first section is a quick, clear review of the policy setting: There are international and national initiatives of uneven design and effectiveness, but the state of California recently enacted the promising California Global Warming Solutions Act (the basis for the San Bernardino suit above), setting targets and associated caps for greenhouse gas emissions. The essay then focuses on transportation as a problem source, accounting as it does for perhaps a third of CO2 emissions in the US, and the fastest growing source at that.

So, what to do about cars and drivers? The candidate policy levers include “better fuel technology, increased vehicle economy, and reducing travel demand.” (p. 21) By far, most progress in relieving car pollution to date resulted from technological fixes. However, the authors calculate that this approach will no longer do the trick. Basically, new cars are already super clean yet VMT will continue to climb with population and trip-generation growth. It is thus not surprising to hear that any reasonable strategy to cut car-generated greenhouse gases in Puget Sound, their case region, must involve substantially less car travel. Indeed, even if mileage grew to an average of 75mpg, the target emission level for 2050 would require that per capita VMT fall by 20%.

Can planners do that? “Demand for car travel can be decreased in several ways, including transit investments, better land-use planning and design, transportation demand management, and road pricing.” (p. 21) “Pricing efforts … and demand management strategies … can be implemented relatively quickly compared to changes in the built environment. However, incentives and disincentives can do little to effect change on their own unless people have reasonable alternatives to driving — such as an efficient transit system for regional travel and land-use patterns that support walking and bicycling for local trips.” (p. 22, emphasis added)

So far, the article is mainly review and context. It identifies a problem. It identifies planning tools: Infrastructure planning, pricing, and land use. The article then focuses on, “Urban form and emissions,” where it makes 3 points:

- “Sprawling urban regions not only encourage automobile use–they require it. Thus many Americans rely on their cars for nearly every commute; shopping, eating, and entertainment trips; and even recreational trips to a park. In contrast, compact communities with a mix of land uses and a highly connected street network are associated with fewer vehicle miles and trips and more bycyling and walking per capita.” (p. 22)

- This result is consistent with the authors’ studies of the Puget Sound region and a comparison of two Seattle area neighborhoods.

- The next phase of their research project will address the question of, “How do alternative approaches to land development and transportation investments affect climate change?”

The article then mainly concludes that,

- “In addition to planning for more walkable areas at the local level, urban regions should coordinate land-use and transportation planning and make substantial investments in transit service, particularly in existing centers….”

- “Urban growth boundaries, urban service areas, distance-based impact fees, creating parking strategies, and infrastructure requirements will also help to reduce reliance on private vehicles and lower per capita carbon dioxide emissions….”

- “The [literature] has also documented other benefits to more compact, walkable urban regions, such as reduced per capita air pollutants and lower obesity rates, which are otherwise becoming serious public health concerns.” (p. 23)

(D) Whatnot:

One, my tent is pitched in the camp of climate scientist colleagues at UCLA, who say global warming is perhaps the greatest environmental threat facing the planet, and that considerable policy changes are advisable to avoid either mayhem or the associated great economic burdens of avoiding mayhem the longer we wait (per the UK’s 2006 Stern report, etc.). They are reasonable, respected, credentialed people all. Indeed, I am participating in a long term project with just that aim: Moving forward, policy-wise, in the climate change debate.

Two, how discretionary land use decisions can best address global warming is virtually unknown in general, notwithstanding what the well-intentioned Frank, Kavage, and Appleyard say to the contrary. The literature is increasingly quite clear on this, whether we like it or not. Indeed, more compact, mixed development can plausibly increase VMT, congestion, and pollution, and reduce physical activity and social capital in the bargain.

I am not saying they will, just as I can’t in all honesty say they won’t — only that your experience will vary, so my own advice to practitioners is to keep their eyes open and avoid generalizing from other places to theirs until they have a good grasp of how well their details fit the story. I am not skeptical of land use strategies to reduce global warming so much as sensitive to the critical details. More and better research will clarify what works and why, what doesn’t and why, and how the details matter. Presenting these as settled questions invites unsophisticated design and implementation of instruments and policies, with uncertain ends. Again, the question is not whether climate change is a pressing planning problem but how best to address it.

In particular places and cases, such strategies can work with more confidence of the desired results — requiring less luck if you will — if done carefully, with attention to local details and behaviors. Put another way, what works in Seattle or San Francisco may be so unhelpful in San Bernardino as to be counterproductive. (For a pdf of my related recent advice to a Beijing audience — with Chinese translation! — on “Top 5 Challenges to Integrating Land Use and Transportation in Urban China,” look among even better presentations in this conference proceeding.)

Three, what I like about these news items: AG Jerry Brown and San Bernardino are making process promises, with attention to local details, and with respect to criteria that feature what is reasonable and what is or is not definitive. While the initial comparison with Marin County was of the apples and oranges variety, this settlement asks planning to be more attentive to climate change issues, without committing to empty promises of what will or won’t work. Yes, hard and fast rules are easier to implement and understand than those based on informed discretion. On the other hand, what if they are wrong?

I also very much like that the Planning article is based more on its research rather than its few idle claims. Laying the data and analysis out plainly makes it possible to confirm or refute the method and results on their merits, and clarifies to practitioners that we generally require supporting evidence. It may draw conclusions from the literature that I do not share, which thankfully gives me something to react to, and so much the better. (Perhaps the Planning editors put the kibosh on ambiguity and elaboration in order to not confuse or bore practitioners.) The article even identifies several open research questions: When was the last time a Planning magazine article did that?

The real low down is that our purpose in these studies and their presentation is to move the data and work forward, making us researchers more valuable, accessible, and transparent to practitioners. The Frank, Kavage and Appleyard essay does that, certainly. If any of the rest of us think we can do better still, go to it.

- Published:

- Monday, August 27th, 2007

- Author:

- randall Crane

- Topics:

- disasters, environment, global warming, land use, law, metrics, mitigation, transportation

Blogroll

- Becker-Posner blog

- BLDG BLOG

- Burb

- CityStates

- Curbed LA

- Cyburbia

- DemocraticSPACE

- Environmental and Urban Economics

- Freakonomics

- LA Transportation Headlines

- Peter Gordon’s Blog

- Planetizen

- The Center for Land Use Interpretation

- The Transportationist

- the urban commons

- This week’s finds in planning

- Urbanicity

Journals

- Cityscape

- environment and planning a,b,c,d

- Harvard Design Magazine

- Housing Policy Debate

- Housing Studies

- International Development Planning Review

- International Journal of Urban and Regional Research

- International Regional Science Review

- Journal of Architectural and Planning Research

- Journal of Housing Economics

- Journal of Planning Education and Research

- Journal of Planning Literature

- Journal of Regional Science

- Journal of the American Planning Association

- Journal of Urban Affairs

- Journal of Urban Economics

- Planning Theory

- Regional Science & Urban Economics

- Transportation Research Parts A,B,C,D,E,F

- Urban Studies

- World Development

8 Comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss | trackback uri